Ah, the Eighteen Forms of Wudang Xuanwu Pai Tai Chi Quan. A subject that whispers of ancient mountains, disciplined practice, and perhaps, as many claim, profound health benefits. But does this modern iteration, born from the needs of policy and popularization, truly encapsulate the *spirit* of Tai Chi, or is it merely a watered-down echo of a forgotten art? Today, we dissect this form, not as a mere tutorial, but as a critical examination of its martial soul and its place in the lineage of true Budo.

The Genesis of the Eighteen Forms

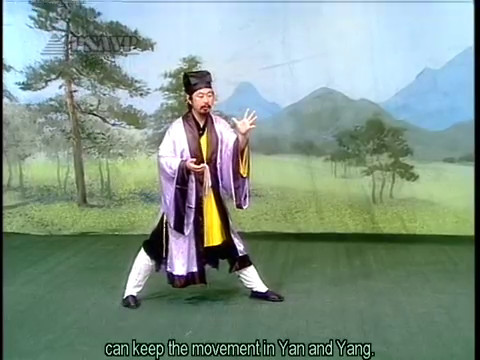

The narrative presented is one of adaptation. The Wudang Xuanwu Pai's Eighteen Forms, we are told, were created by Master Yang Qun Li, supported by the state athletic Wushu department, to meet the demands of a global audience and a national policy advocating for widespread athletic exercise. Later, Master You Xuande refined it into a simplified version, launching a campaign across China. This routine, approved by the headmaster himself, You Xuande, is now practiced by his disciples and is a uniform routine in Wudang competitions.

This origin story is, frankly, a double-edged sword. On one hand, it speaks to the adaptability and enduring appeal of Tai Chi principles. On the other, it immediately raises the critical question: When an art form is "created" to meet external policy and policy, does it risk losing the very essence it claims to represent? Is it a natural evolution, or a concession to the marketplace?

"The Way of the warrior is to learn to die." - Miyamoto Musashi

While Musashi spoke of the sword, this principle of confronting one's own potential demise – a metaphor for confronting weakness and ego – is central to any art that claims martial depth. Does the Eighteen Forms routine retain this confrontation, or does it prioritize accessibility over existential rigor?

The form is said to incorporate essentials from the Old Frame Tai Ji Quan, Tai Yi Zhang, Mian Zhang, Wu Xing Yang Sheng Gong, Xing Yi Quan, and Ba Gua Zhang. This is an ambitious blend. The question remains: does it skillfully weave these threads into a coherent tapestry, or is it a superficial sampling of diverse martial philosophies?

Martial Essence: Fact or Fiction?

Herein lies the heart of my critique. Many modern Tai Chi forms, especially those promoted for health or competition, have, in my observation over decades of study and practice, de-emphasized or outright removed the martial applications. The flowing, elegant movements can be beautiful, but are they *effective*? Can the principles of song (relaxation), jing (intent), and fa jin (explosive power) truly be honed through a form designed for mass appeal?

The Xuanwu Pai's Eighteen Forms, by its very name and historical context, should retain a connection to its roots. Wudang Tai Chi is traditionally one of the most martial styles. However, the "creation" and "simplification" for broader accessibility often come at a cost. Was the original Wudang boxing, from which this form is derived, a robust martial art, or was it already a stylized dance? And if it was martial, what specific martial principles are preserved, and to what degree?

Let us consider the core concepts. Tai Chi Quan, in its purest form, is a sophisticated combat system disguised as a slow-moving exercise. It relies on yielding, redirecting an opponent's force, and striking at the opportune moment with immense power. The circular movements are not just for aesthetic flow; they are designed to evade, trap, and deliver strikes from unexpected angles. The footwork, often seen as merely decorative, is crucial for maintaining balance, generating power, and controlling distance.

Does the Eighteen Forms routine emphasize these elements? Or does it, like many contemporary interpretations, focus on the health benefits, the large movements, and the meditative aspects, leaving the combative core underdeveloped? My concern is that if the martial applications are not understood, practiced, and integrated, the form becomes mere shadow boxing. It's a beautiful shell, perhaps, but empty of the fire that defines a true martial art.

Beyond the Movements: The Philosophical Core

The philosophy of Tai Chi Quan is deeply intertwined with Taoist principles: harmony, balance, and the interplay of yin and yang. The slow, deliberate movements are meant to cultivate mindfulness, allowing the practitioner to become aware of their body, their energy (Qi), and their surroundings. This heightened awareness is not just for combat; it’s a path to self-understanding and inner peace.

The inclusion of elements from Xing Yi Quan and Ba Gua Zhang in the Eighteen Forms is particularly interesting. Xing Yi Quan, known for its direct, explosive linear movements, contrasts with the circularity of Tai Chi. Ba Gua Zhang is characterized by its evasive circular stepping and palm strikes. A masterfully constructed form would integrate these differing principles seamlessly, reflecting the Taoist concept that opposites are complementary and can coexist. However, a poorly integrated form might feel disjointed, a mere collage of styles rather than a unified expression of martial philosophy.

The concept of Wu Wei (non-action or effortless action) is central to Taoism and, by extension, to Tai Chi. It is not about doing nothing, but about acting in accordance with the natural flow of things. In combat, this means not forcing movements, but using the opponent's energy against them. In daily life, it means acting without unnecessary effort or resistance.

The question then becomes: does the practice of the Eighteen Forms foster this understanding of Wu Wei? Or does the emphasis on performance, competition, and achieving a certain number of repetitions lead to a more forceful, goal-oriented approach that contradicts this core philosophical tenet?

Training Guide: Essential Principles for the Eighteen Forms

Regardless of the form's origin, the principles of diligent training remain universal. For any practitioner engaging with the Wudang Xuanwu Pai's Eighteen Forms, or indeed any Tai Chi style, these fundamentals are paramount:

- Rooting (Zhan Zhuang): Before any movement, one must learn to stand. Practice standing meditation (Zhan Zhuang) for extended periods. Feel your connection to the earth. This is the foundation of all power and stability. Without a strong root, any technique is easily overthrown.

- Relaxation (Song): Tension is the enemy of Tai Chi. Learn to release unnecessary muscular tension, allowing Qi to flow freely. Your movements should be like water, yielding and adapting, not like rigid steel.

- Intention (Yi): Every movement must have a clear intention. This is not just about moving your arms and legs; it is about directing your mind and energy. Visualize the application of each posture, even in a solo form.

- Structure and Form: While the Eighteen Forms may be a "new frame," understanding the fundamental structural principles of Tai Chi is crucial. Pay attention to the alignment of your spine, the position of your hips, and the coordination of your entire body.

- Breathing: Natural, deep breathing is essential. Coordinate your breath with your movements – often exhaling on exhalation of force and inhaling on gathering energy.

- Repetition with Awareness: Repetition is key to muscle memory and deeper understanding. However, mindlessly repeating the form is insufficient. Each repetition should be an opportunity for refinement, for correcting posture, and for deepening your connection to the principles.

- Application (Yongfa): If possible, seek instruction from a qualified teacher who can explain and demonstrate the martial applications of each movement. Without understanding the 'why' behind the 'how', the form remains incomplete.

This structured approach ensures that even a simplified form can be a profound training tool, rather than a mere set of motions.

Veredict of the Sensei: Is it True Tai Chi?

This is where I risk ruffling feathers, but a true Sensei does not shy away from uncomfortable truths. The Wudang Xuanwu Pai's Eighteen Forms represents a fascinating intersection of tradition, policy, and popularization. Its creation demonstrates the enduring relevance of Tai Chi's principles in a modern context, seeking to promote health and accessibility globally.

However, "True Tai Chi" is a term laden with historical and martial significance. If the Eighteen Forms prioritizes ease of learning and broad appeal over the rigorous martial applications and deep philosophical underpinnings that characterized its ancestors, then it is, at best, a distant cousin. At worst, it is a dilution that risks losing the very soul of the art.

I cannot definitively label it "true Tai Chi" without experiencing its practical application firsthand, guided by a master who embodies its martial lineage. However, based on the narrative of its creation and common trends in modern martial arts popularization, my skepticism remains high regarding its martial depth. It may be an excellent *exercise* and a valuable tool for health and meditation, but whether it truly prepares one for combat or imparts the full philosophical weight of traditional Tai Chi is highly debatable.

Rating: Slightly better than a shadow, but still searching for its fangs.

Essential Equipment for Your Training

While Tai Chi is often lauded for its accessibility and minimal equipment needs, certain items can enhance your practice and deepen your understanding:

- Comfortable Training Attire: Loose-fitting, breathable clothing is paramount. This allows for freedom of movement and prevents restriction. Look for natural fabrics like cotton or linen.

- Tai Chi Shoes or Grippy Socks: Proper footwear is crucial for stability and preventing slips. Traditional Tai Chi shoes offer a thin, flexible sole that allows you to feel the ground. If unavailable, socks with good grip are a viable alternative for indoor practice.

- A Supportive Sensei or Community: Perhaps the most critical "equipment" is guidance. Finding a qualified instructor who understands the martial aspects of Tai Chi, or a dedicated training group, is invaluable.

- Reference Materials: Books or high-quality instructional videos (though often a poor substitute for live instruction) can aid in understanding the forms and principles.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is the Wudang Xuanwu Pai's Eighteen Forms a traditional Tai Chi form?

A: While it draws from Wudang Tai Chi traditions, it is described as a "new frame" created in recent times for broader appeal and policy alignment, making its "traditional" status debatable in the strictest sense.

Q2: Can this form be used for self-defense?

A: Its effectiveness for self-defense depends heavily on the practitioner's understanding and emphasis on martial applications, which may be de-emphasized in favor of health benefits and aesthetics in this particular iteration.

Q3: What is the difference between this form and Yang-style Tai Chi?

A: Yang-style is one of the most widely practiced forms, known for its large, open, and evenly spaced movements. The Eighteen Forms, being a Wudang creation, may incorporate different structural principles and historical lineages, alongside elements from other internal arts.

Q4: How long does it take to learn the Eighteen Forms?

A: Learning the sequence can take weeks or months, but truly mastering its principles, including martial applications and philosophical depth, is a lifelong pursuit.

To Deepen Your Path

The journey into the heart of martial arts is a continuous one. If the principles discussed here resonate with you, I encourage you to explore further:

Sensei's Reflection: Your Next Step

So, we have examined the Wudang Xuanwu Pai's Eighteen Forms. It stands as a testament to the adaptability of martial arts, but also as a cautionary tale. Is the pursuit of wider accessibility worth the potential dilution of martial depth and philosophical rigor? Does a form created for policy and popular appeal truly honor the spirit of Budo?

Consider this: If your goal is merely physical exercise, then perhaps this form, or any form, will suffice. But if you seek the path of the warrior, the profound self-discovery, and the practical application of ancient principles – the true essence of martial arts – then you must look deeper. You must question the origins, demand the martial applications, and seek out those who uphold the integrity of the art.

Your challenge: Next time you practice a form, whether it is the Eighteen Forms or any other, ask yourself: "What is the purpose of this movement? How could this be used in defense? What philosophical principle does it embody?" Do not accept movements at face value. Seek the meaning. Prove me wrong in the comments below, or perhaps, prove me right.

```

GEMINI_METADESC: Explore the Wudang Xuanwu Pai's Eighteen Forms Tai Chi. A Sensei's critical analysis of its martial essence, philosophical depth, and place in true Budo. Does tradition yield to policy?