The true warrior does not seek to conquer, but to understand the nature of conflict itself. Only then can true defense be achieved.

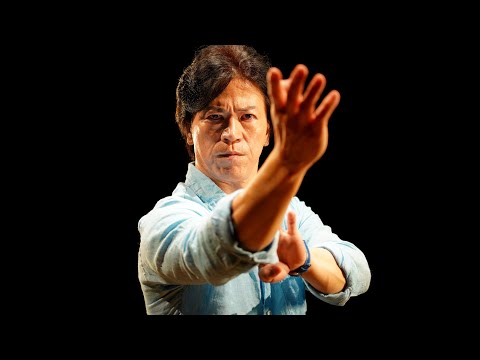

Welcome, students of Budo and the martial arts. Today, we delve into a subject that often sparks fervent debate: the practical application of traditional techniques in modern self-defense. You are watching a presentation on the self-defense techniques of Kung Fu, specifically focusing on Qin-na, ramming attacks, and pressure points, as demonstrated by the esteemed Tamotsu Miyahira. Published on May 16, 2022, this content aims to showcase a specific facet of martial science. But is it merely a demonstration, or a true lesson in survival? Let us dissect this, as we always do, with a critical eye and an unyielding pursuit of truth.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Pragmatism of Qin-na

- Qin-na: More Than Just Joint Locks?

- The Ramming Attack: Brutal Efficiency or Over-Reliance?

- Pressure Points: The Art of Disabling the Adversary

- Analyzing Miyahira's Demonstration

- Bridging the Gap: From Dojo to Street

- Training Guide: Developing Qin-na Sensitivity

- Equipment Essential for Your Training

- Veredicto del Sensei: Does it Defend?

- Frequently Asked Questions

- To Deepen Your Path

- Sensei's Reflection: Your Next Step

Introduction: The Pragmatism of Qin-na

The world of martial arts is vast, a tapestry woven with threads of ancient philosophy, rigorous physical training, and sometimes, pure myth. Today, we examine techniques that reside in the realm of Kung Fu, specifically Qin-na, often translated as "grappling and controlling" or "seize and grasp." This system of joint manipulation, along with ramming attacks and the application of pressure points, forms the core of the demonstration by Tamotsu Miyahira. My intent here is not merely to describe, but to critically analyze the efficacy and underlying principles of these methods, asking ourselves: Do they stand up to the harsh realities of a confrontation?

We are on the internet's most comprehensive and updated martial arts blog. Follow us on social networks and don't forget to visit our main page: Budo and Martial Arts. The pursuit of practical self-defense is a noble one, yet it is fraught with misconceptions. Many practitioners become enamored with complex techniques seen in films or demonstrations, only to find them useless when faced with genuine danger. My role as your Sensei is to cut through the flourish and expose the substance. Let us begin by understanding the mechanics and philosophy behind Qin-na.

Qin-na: More Than Just Joint Locks?

Qin-na (擒拿) is not a single technique, but rather a family of methods designed to control an opponent by manipulating their joints, tendons, and ligaments. It's a critical component of many Southern Chinese martial arts, including Wing Chun and Hung Gar. At its core, Qin-na seeks to exploit the body's natural vulnerabilities. By applying pressure to specific joints or by trapping limbs, practitioners aim to immobilize, injure, or even break an opponent's structure without necessarily resorting to devastating strikes.

The inherent beauty of Qin-na lies in its subtlety. It doesn't require brute strength, but rather an understanding of leverage, timing, and the opponent's balance. A well-executed Qin-na technique can neutralize a much larger and stronger assailant. However, its effectiveness is highly dependent on several factors:

- Proximity: Qin-na requires close-range engagement, which can be dangerous if the opponent is also a skilled striker.

- Timing: The moment of opportunity to apply a lock or trap is fleeting. Hesitation or a missed cue can lead to a failed technique.

- Training Intensity: Qin-na is not something learned from a video alone. It demands repetitive practice to develop the feel, sensitivity, and muscle memory necessary for its application.

- Adaptability: A rigid application of a specific lock will fail against a resisting opponent. True Qin-na practitioners must be able to adapt to the opponent's reactions.

The popular misconception is that Qin-na is solely about twisting arms into unnatural positions. While this is part of it, advanced Qin-na also involves understanding the body's structure, nerve points, and leverage to control movement and create openings for strikes or takedowns. It’s a sophisticated system that, when properly trained, can be incredibly effective.

The Ramming Attack: Brutal Efficiency or Over-Reliance?

Ramming attacks, often seen as a more direct and forceful application of Kung Fu principles, involve using the body – particularly the shoulders, hips, and forearms – to deliver a powerful, concussive blow. Think of a bull charging or a battering ram against a door. In combat, this can manifest as a shoulder charge to disrupt an opponent's balance, a hip throw to unseat them, or a forearm strike to the chest or solar plexus.

The appeal of the ramming attack is its simplicity and the raw power it can generate. When executed correctly, it can create immediate space, knock an opponent off their feet, or even incapacitate them through sheer force. However, and this is where my critical analysis comes into play, such attacks carry significant risks:

- Self-Injury: A poorly executed ramming attack can result in injury to the attacker, particularly to the shoulder or knee.

- Vulnerability: Committing to a full ramming attack leaves the attacker open to counter-attacks, especially if they miss their target or the opponent is adept at evasive maneuvers.

- Context Dependency: While effective against a stationary or unbalanced opponent, it can be less effective against a mobile or skilled combatant who anticipates the move.

Many styles incorporate these forceful entries, but the key is understanding *when* and *how* to apply them. Is it a primary method of attack, or a tool to create opportunities for other techniques? The demonstration by Miyahira might shed some light on this, but the true test lies in its application under duress.

Pressure Points: The Art of Disabling the Adversary

Pressure point striking, or Dim Mak (點脈), is perhaps one of the most mythical and controversial aspects of Chinese martial arts. The concept is that by striking specific points on the body, one can disrupt the flow of "Qi" (vital energy), causing pain, paralysis, or even death. While the more esoteric claims of Dim Mak often veer into fantasy, the underlying principle of targeting vulnerable anatomical structures – nerve clusters, arteries, soft tissue – is undeniably real and forms a basis for many pressure point techniques.

In practical self-defense, understanding these points can be a powerful tool. Targeting the eyes, throat, groin, or the nerves in the arm and leg can quickly incapacitate an attacker, providing a crucial window for escape. The danger with pressure points, however, lies in:

- Accuracy: Identifying and striking these points accurately, especially under the stress of a fight, requires immense precision and knowledge.

- Variability: The effectiveness can vary greatly from person to person due to differences in body mass, pain tolerance, and even the angle of the strike.

- Misinformation: The mystical aura surrounding Dim Mak has often led to exaggerated claims and ineffective training methods.

A grounded approach recognizes that pressure point striking is a form of targeted trauma, akin to a well-placed blow in boxing or kickboxing. It's about exploiting anatomical weaknesses for tactical advantage, not about wielding mystical powers.

Analyzing Miyahira's Demonstration

Tamotsu Miyahira is a respected figure in the martial arts community, and his dojo is known for its focus on practical application. When observing his demonstrations of Qin-na, ramming attacks, and pressure points, we must look beyond the surface. Are these techniques performed with crisp precision and clear intent? Does the demonstration convey the *how* and the *why*, or is it simply a display of ability?

I would analyze the footage from a critical perspective:

- Clarity of Technique: Are the joint locks applied smoothly, or do they appear forced? Is the ramming attack delivered with conviction and proper body mechanics? Are the pressure point strikes precise and well-aimed?

- Response to Resistance: In a controlled demonstration, the opponent often cooperates to some degree. Does Miyahira's technique show how it would work against active resistance, or is it against a passive partner?

- Contextualization: Does the demonstration provide scenarios for when these techniques would be most effective? For example, is Qin-na shown as a transition from a grab, or is the ramming attack presented as a direct assault?

- Underlying Principles: Does the demonstration implicitly or explicitly teach the principles of leverage, balance disruption, and anatomical vulnerability, rather than just the mechanics of the move?

The YouTube channel associated with Miyahira Dojo, and the wider KURO-OBI WORLD INTERNATIONAL SERVICE, offers a platform for practitioners to share their knowledge. The availability of subtitles in multiple languages is commendable, democratizing access to these lessons. However, as I always stress, passive viewing is insufficient. True learning requires active engagement and, crucially, practical application under the guidance of a qualified instructor.

Bridging the Gap: From Dojo to Street

This is where the most crucial discussion lies. How do techniques like Qin-na, ramming attacks, and pressure points translate from the controlled environment of a dojo to the chaotic reality of a street confrontation? The answer, as with most things in martial arts, is: it depends.

Qin-na in a self-defense scenario often needs to be simpler and more direct than the intricate variations shown in some forms. A basic wrist lock or a limb trap applied effectively can create an escape opportunity. However, attempting complex joint manipulations against a determined attacker can be a recipe for disaster. The opponent might break free, reverse the hold, or simply continue their assault while you are struggling with the lock.

Ramming attacks can be effective, especially as an initial shock or to create space when overwhelmed. A well-timed shoulder barge can knock an attacker off balance, opening them up for a follow-up or allowing for an escape. However, initiating a ramming attack without proper setup or against a more skilled opponent can leave you vulnerable to takedowns or strikes.

Pressure points are often the most romanticized and least consistently applicable. While a precise strike to a vulnerable nerve can be debilitating, the margin for error is tiny. In a high-stress situation, achieving that pinpoint accuracy is incredibly difficult. It's far more likely that a general strike to a sensitive area (like the groin or throat) will yield more reliable results for the average practitioner.

The key takeaway is that these techniques, while possessing inherent merit, require:

- Simplicity: Complex sequences are less likely to be recalled and executed under duress.

- Directness: Techniques should aim for a clear, immediate effect, whether it's control, incapacitation, or escape.

- Integration: These methods are often most effective when integrated with striking and defensive footwork, not practiced in isolation.

- Realistic Training: Sparring that incorporates elements of grappling, close-quarters striking, and resistance is essential.

Training Guide: Developing Qin-na Sensitivity

Developing the feel and precision required for Qin-na is paramount. This isn't learned by simply watching; it requires dedicated practice. Here’s a fundamental approach:

- Partner Drills: Find a trusted training partner. Begin with basic grips and holds.

- Controlled Resistance: One partner applies a grip or a simple lock, while the other offers mild, controlled resistance. The goal is for the attacker to feel how to adapt their pressure and leverage to maintain control.

- Sensitivity Exercises: Practice "listening" with your hands. When your partner moves, you should feel the shift in their weight and tension. This is the foundation of effective Qin-na.

- Anatomical Study: Understand the major joints (elbow, wrist, shoulder) and common stress points. Learn about the basic mechanics of hyperextension and flexion.

- Repetition: Practice the same few core techniques repeatedly until they become second nature. Focus on smooth transitions and efficient application of force.

- Gradual Increase in Resistance: As sensitivity develops, slowly increase the level of resistance from your partner. This helps bridge the gap towards more realistic scenarios.

Remember, the goal is not to injure your partner, but to develop the fine motor skills and proprioception necessary for control. Think of it as learning to tune a delicate instrument.

Equipment Essential for Your Training

While many traditional martial arts emphasize training with minimal equipment, certain items can significantly enhance your practice, particularly for techniques like Qin-na and general conditioning.

- Durable Training Uniform (Gi): A strong, double-weave uniform is essential for practicing grips and controlling your partner without the gi tearing. For styles like Judo or Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, a high-quality Gi is non-negotiable. Look for brands known for their durability.

- Grappling Dummy: While not a substitute for a live partner, a grappling dummy can be invaluable for practicing throws, joint locks, and submissions without needing a partner present.

- Wrist Wraps/Supports: For Qin-na training, where wrist and elbow manipulation is key, wrist wraps can offer support and help prevent minor injuries as you build strength and technique.

- Mats (Tatami/Judo Mats): Crucial for safety, especially when practicing throws or techniques that might lead to falls.

- Training Weights/Resistance Bands: For building the specific strength and endurance needed for sustained grappling and control techniques.

Investing in quality gear is investing in your longevity and safety as a martial artist. Look for reputable brands specializing in martial arts equipment.

Veredicto del Sensei: ¿Merece la pena?

Tamotsu Miyahira's demonstration offers a valuable glimpse into specific Kung Fu self-defense techniques: Qin-na, ramming attacks, and pressure points. The technical proficiency is evident, and the accessibility via multiple languages is a significant plus for the global Budo community. However, as a tool for practical self-defense, its effectiveness is highly conditional.

Qin-na, when taught and practiced with emphasis on sensitivity, leverage, and adaptability, can be a potent tool. Miyahira's demonstration likely showcases this potential, but the true learning lies in the hours of dedicated practice within a structured curriculum.

Ramming attacks offer a direct, forceful solution, but require careful timing and understanding of risk/reward to avoid self-injury or vulnerability.

Pressure points, while having a basis in anatomical vulnerabilities, are the least reliably applicable in a chaotic street fight due to the required precision.

Overall Assessment: A valuable educational resource for martial artists seeking to understand specific Kung Fu applications. However, it should be viewed as a *component* within a broader self-defense strategy, not a complete solution. Its true value is unlocked through diligent, realistic training under expert guidance.

Calificación: Cinturón Negro en Demostración, Marrón en Aplicación Directa sin Entrenamiento Adicional.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is Qin-na practical for self-defense against an untrained attacker?

A1: Yes, basic Qin-na techniques can be very effective against an untrained attacker because they exploit natural vulnerabilities. However, complex variations require significant training.

Q2: Can ramming attacks cause serious injury to the attacker?

A2: A forceful ramming attack can injure the attacker's joints (shoulder, knee) or lead to them being thrown off balance. However, improper execution poses a greater risk of self-injury.

Q3: Are pressure point techniques effective in real fights?

A3: While striking vulnerable points can cause pain or incapacitation, the precision required often makes them difficult to execute effectively under extreme stress. Simpler, more direct strikes to sensitive areas are generally more reliable for the average practitioner.

Q4: How can I learn these techniques safely?

A4: The best way is to find a qualified instructor who teaches these specific arts or applications. Safe, realistic training involves progressively increasing resistance and understanding the principles behind the techniques, not just memorizing movements.

To Deepen Your Path

To truly understand the depth and breadth of martial philosophy and practice, I encourage you to explore these related topics:

- Defensa Personal: Principles Beyond Techniques

- The Core Philosophy of Budo: More Than Just Fighting

- MMA Training: Integrating Striking and Grappling

Sensei's Reflection: Your Next Step

We have dissected Qin-na, ramming attacks, and pressure points, analyzing their potential and their pitfalls. Miyahira's demonstration offers a window, but the true essence of these techniques is not in the viewing, but in the diligent, often arduous, practice.

Sensei's Reflection: Your Next Step

Now, consider this: If a technique, no matter how ancient or revered, fails to provide a tangible advantage in a moment of true need, has it served its purpose? Or has it become mere performance?

Your challenge: Reflect on one technique you have trained extensively. Does it rely on intricate movements or fundamental principles? Under pressure, would it work, or would it leave you vulnerable? Go to the mat, physically or mentally, and find the honest answer. Then, come back and tell me.

``` GEMINI_METADESC: Critically analyze Tamotsu Miyahira's Kung Fu self-defense techniques (Qin-na, ramming, pressure points). Explore their real-world applicability, training methods, and effectiveness in combat.