Table of Contents

- The Genesis: Tracing the Historical Lineage

- The Philosophical Core: Aiki and its Application

- Techniques and Principles: The Daitō-ryū Arsenal

- The Takeda Legacy: Guardians of the Art

- Daitō-ryū vs. Modern Judo: A Polemic Debate

- Training Essentials for the Aspiring Daitō-ryū Practitioner

- Resources for Deeper Study

- Veredicto del Sensei: The Enduring Spirit of Daitō-ryū

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Explore Further on Your Path

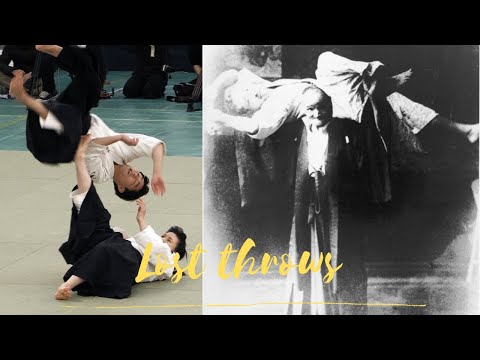

What truly defines an art form? Is it the flashy techniques, the ancient lineage, or the philosophical underpinnings that transcend mere physical combat? Today, we delve into the intricate world of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu (大東流 合気柔術), an art shrouded in history and often misunderstood. Many practitioners flock to its modern interpretations or confuse it with its more globally recognized descendant, Judo. But is this simplification doing justice to the profound martial science that the Takeda family has preserved for generations?

Our journey today is not merely an academic exploration; it's a dissection. We will examine the historical claims, the practical application of its core principles, and challenge the common misconceptions that often surround this venerable art. Are you ready to look beyond the surface and understand the true essence of Daitō-ryū?

The Genesis: Tracing the Historical Lineage

The narrative of Daitō-ryū is inextricably linked to the Takeda family of the Aizu Domain. Legend and historical accounts place its origins within the samurai class, specifically with the techniques of the Yari (spear) and the Tachi (sword) being adapted for unarmed combat. It is said that Minamoto no Yoshimitsu, also known as Shinra Saburō Minamoto no Yoshikiyo Takeda, a prominent samurai of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), is the progenitor of the art. He is credited with developing a unique system of self-defense techniques based on his observations and study of combat, which he later systematized and passed down through his descendants.

The name "Daitō-ryū" itself, meaning "Great Eastern Flow," hints at its perceived prominence and perhaps its geographical roots. The art was meticulously preserved within the Takeda family for centuries, passed down through generations in relative obscurity. It wasn't until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the art began to be shared more widely, primarily through the efforts of Sokaku Takeda, who is considered the last true headmaster (Sōke) of the system as it was traditionally practiced.

Sokaku Takeda was a formidable martial artist who traveled extensively throughout Japan, honing his skills and, importantly, disseminating his knowledge. It was during this period that many prominent martial artists studied under him, including Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido. This connection is crucial, as it explains the shared principles and many overlapping techniques between Daitō-ryū and Aikido. However, the emphasis, the pedagogical approach, and the ultimate objectives often diverge significantly.

"The true warrior is one who can embody the principles of the art even when unarmed, for the highest expression of strategy is found in the absence of weapons." - Attributed to historical samurai strategists.

Understanding this historical progression is key. Daitō-ryū is not merely a collection of throws and joint locks; it is a system born from the battlefield realities faced by samurai, adapted for the protection of oneself and one's lord. Its techniques were designed to be effective against armed opponents, requiring a deep understanding of body mechanics, timing, and the application of subtle yet powerful force.

The Philosophical Core: Aiki and its Application

At the heart of Daitō-ryū lies the concept of Aiki (合気). Often translated as "harmonious energy" or "joining energy," Aiki is not some mystical force, but rather a sophisticated principle of leverage, timing, and blending with an opponent's movement. It's about understanding how to use the opponent's own power, momentum, and intention against them.

This is where the controversy often ignites. Many contemporary martial arts systems focus on brute strength or overpowering an opponent. Daitō-ryū, conversely, emphasizes achieving control and neutralizing an attack through minimal effort. This doesn't mean it's easy; it requires immense internal development, proprioception, and a deep understanding of anatomy and physics.

Consider the common scenario of an opponent attempting a forceful grab or strike. A Daitō-ryū practitioner doesn't meet force with equal force. Instead, they might redirect the opponent's line of attack, subtly shift their own center of gravity, and use a small, precise movement to unbalance them, leading to a joint lock or throw. This is the essence of Aiki: a seemingly effortless control born from an intelligent application of principles.

The philosophy extends beyond physical technique. It’s about cultivating a mindset – a state of awareness and calm under pressure. This mental fortitude, akin to the Buddhist concept of Mushin (無心), or "no mind," allows the practitioner to react spontaneously and effectively without hesitation or conscious thought. It's a state achieved through rigorous training and a deep internalization of the art's principles.

Techniques and Principles: The Daitō-ryū Arsenal

Daitō-ryū's technical repertoire is vast and intricate, often categorized into various sets of waza (技), or techniques. These include:

- Kuzushi (崩し): Unbalancing the opponent. This is the foundational principle; without proper kuzushi, subsequent techniques are significantly weakened.

- Uke Nagashi (受け流し): Receiving and deflecting. This involves absorbing and redirecting an incoming attack rather than blocking it head-on.

- Atemi (当身): Striking techniques, often used to disrupt the opponent's balance, timing, or awareness, facilitating other techniques. While not always the primary focus in some interpretations, their strategic use is crucial.

- Kansetsu Waza (関節技): Joint locks. These are designed to control or incapacitate an opponent by manipulating their joints.

- Shime Waza (絞技): Choking techniques. Used to control or subdue an opponent through restricted breathing.

- Nage Waza (投げ技): Throwing techniques. These are often subtle, leveraging the opponent's imbalance and momentum.

A common misunderstanding is that Daitō-ryū is simply a precursor to Judo, with Judo having adopted and refined its throwing techniques. While Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo, did study Daitō-ryū under Sokaku Takeda, he selectively extracted and systematized certain elements, emphasizing sport and safety. Daitō-ryū, in its traditional form, retains elements that are less suited for a sporting context but are arguably more effective for self-defense or combat situations, such as the integration of atemi and a wider range of joint manipulation techniques, often applied to multiple joints and in more complex sequences.

The Takeda Legacy: Guardians of the Art

The Takeda family's role in preserving Daitō-ryū is paramount. Sokaku Takeda (1859-1943) is the pivotal figure who brought the art to a wider audience. He was known for his intense training methods and his unwavering dedication to the art. His son, Tokimune Takeda (1916-1988), continued his father's legacy, further systematizing the curriculum and ensuring its transmission.

However, the history is not without its complexities and controversies. Disputes over succession, interpretations of the curriculum, and the very definition of "true" Daitō-ryū have led to the emergence of various branches and lineages. Some prominent figures who studied under Sokaku Takeda, such as Morihei Ueshiba (Aikido) and Choi Yong-Sool (Hapkido), developed their own distinct martial arts, incorporating principles learned from Daitō-ryū but evolving them in unique directions.

This diversification, while enriching the martial landscape, also leads to fragmentation. Today, practitioners might encounter Daitō-ryū Kodokai, Daitō-ryū Aikijujutsu Shimbokukai, and other variations, each with its own emphasis and approach. Authenticity often becomes a point of contention, leading practitioners to question which lineage truly upholds the spirit of Sokaku Takeda.

"The path of mastery is not a straight line, but a winding river. Each bend reveals new currents, new challenges, and new depths to explore. Do not fear the change; embrace the flow." - A teaching from the Daitō-ryū tradition.

Daitō-ryū vs. Modern Judo: A Polemic Debate

This is where the real fire can be stoked. Judo, as a sport, has evolved dramatically. Its emphasis on dynamic throws and ground grappling (Ne-Waza) has made it a globally popular Olympic discipline. However, in this pursuit of sport, certain aspects that were integral to its Daitō-ryū roots have been deemphasized or removed.

Daitō-ryū, on the other hand, is not bound by the constraints of a sporting competition. Its curriculum often includes techniques and strategies that are dangerous for sparring, such as certain joint locks applied to vulnerable points, striking techniques designed to incapacitate, and a more direct application of Aiki to control and subdue. The intent is often self-preservation or the effective neutralization of a threat, rather than scoring points.

Is modern Judo less effective? Absolutely not, in its own domain. It fosters incredible discipline, physical conditioning, and formidable grappling skills. But to equate it directly with the broader, more combative scope of Daitō-ryū is a fallacy. One is a refined sport; the other is a comprehensive martial art system designed for a wider range of conflict scenarios.

Furthermore, the modern emphasis on specific grips and attack-response drills in Judo might inadvertently train practitioners to become predictable, a weakness that a skilled Daitō-ryū practitioner could exploit. This isn't to disparage Judo, but to highlight the distinct evolutionary paths and objectives of these related arts.

Training Essentials for the Aspiring Daitō-ryū Practitioner

Embarking on the path of Daitō-ryū requires a different approach than training for a sport. The focus is on internal development and understanding principles, not just rote memorization of techniques. Here's what you'll need:

- A Qualified Instructor: This is non-negotiable. Finding a legitimate lineage instructor is paramount. Beware of individuals claiming mastery without verifiable lineage or extensive training under recognized masters.

- Patience and Persistence: Daitō-ryū is not learned overnight. It requires years of dedicated practice to internalize the subtle principles.

- Open Mind: Be willing to unlearn preconceived notions about martial arts. The principles of Aiki can be counter-intuitive at first.

- Proper Attire: A durable kimono (gi) designed for grappling arts is essential. Look for a thick, double-weave fabric that can withstand the rigors of joint locks and throws. While specific Daitō-ryū uniforms exist, a high-quality judo or Jiu-Jitsu gi will suffice in most cases.

- Training Partner(s): Consistent practice with committed partners is vital for developing timing, sensitivity, and the ability to apply techniques safely and effectively.

Resources for Deeper Study

While direct instruction is key, supplementing your training with research can accelerate your understanding. Here are some avenues:

- Books on Daitō-ryū: Seek out well-researched historical accounts and technical manuals. Be critical of sources that sensationalize or misrepresent the art.

- Biographies of Masters: Studying the lives and philosophies of Sokaku Takeda, Tokimune Takeda, and other significant figures can offer profound insights.

- Comparative Martial Arts Studies: Understanding the historical and technical relationships between Daitō-ryū, Aikido, Judo, and other related arts can provide valuable context.

Veredicto del Sensei: The Enduring Spirit of Daitō-ryū

Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu represents a significant chapter in the history of Japanese martial arts. It is a system born from the pragmatic needs of the samurai, emphasizing subtlety, principle, and the intelligent application of force. While its direct lineage and interpretation may be debated, its influence is undeniable, resonating through modern arts like Aikido and Judo.

As a martial art, its value lies not just in its physical techniques, but in the philosophical and mental discipline it cultivates. It challenges practitioners to think differently about conflict, about leverage, and about their own internal capabilities. It demands dedication, introspection, and a deep respect for tradition.

Is it for everyone? Perhaps not. Those seeking purely sport-oriented training might find Judo or BJJ more immediately rewarding. But for the dedicated martial artist who seeks a deeper understanding of classical combat principles, an exploration into Daitō-ryū offers a rich and rewarding, albeit challenging, path.

Rating: Master of Subtle Force (Menkyo Kaiden in Principles)

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the primary difference between Daitō-ryū and Aikido?

- While both share roots and principles of Aiki, Aikido, founded by Morihei Ueshiba (a student of Sokaku Takeda), emphasizes harmonizing with an attacker's energy for peaceful resolution and de-escalation. Daitō-ryū, in its traditional form, often retains a more direct, combative focus, incorporating strikes and a broader range of joint manipulations aimed at effective neutralization.

- Can Daitō-ryū techniques be used in modern self-defense?

- The underlying principles of balance, leverage, and timing are universally applicable. However, some specific techniques might be too complex or dangerous to apply under the extreme stress of a real-world encounter without extensive, realistic training. Adaptability and understanding the core principles are key.

- Is Daitō-ryū dangerous to practice?

- Like all robust martial arts, it carries inherent risks, especially due to the joint locks and potential for impact. However, under the guidance of a qualified instructor and with committed training partners who practice safely, the risks can be managed. Safety is a cornerstone of responsible martial arts training.

- Where can I find a Daitō-ryū dojo?

- Finding a legitimate dojo requires diligent research. Look for instructors who can clearly articulate their lineage back to Sokaku Takeda through recognized channels. Websites of major Daitō-ryū organizations (e.g., Kodokai, Shimbokukai) can be starting points, but always verify credentials and visit the dojo if possible.

Explore Further on Your Path

Reflexión del Sensei: Your Next Step

We have dissected the lineage, examined the philosophy, and debated its place in the modern martial landscape. But knowledge without application is like a sword left to rust. The question that now hangs in the air, heavy with the weight of tradition and the edge of innovation, is this: How will you integrate the principles of subtle force and unwavering principle into your own training, not just as techniques, but as a way of being?

``` GEMINI_METADESC: Explore the rich history and profound philosophy of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu. Understand its lineage, techniques, and its distinct place among classical martial arts.